Adaptation benefits are in a similar position today to that of emission reductions in the 1990s, when the international community was broadly aware that greenhouse gas emissions had to be reduced, but the available technologies and know-how, such as renewable energy generation, were not financially attractive and no large-scale mechanisms existed to encourage their adoption.

Mitigation benefits, by contrast, are well defined. There are several mechanisms to legislate, recognize, incentivize or reward ways to reduce emissions. Results-based payment mechanisms for mitigation, notably the Clean Development Mechanism, provided market opportunities for project developers to access new financing that radically altered project economics and led to the acceptance and mainstreaming of ‘low carbon’ technologies, many of which are now commercially viable. However, while adaptation technologies and solutions are emerging, many are not (yet) financially attractive, and some do not generate cash incomes.

Like mitigation benefits, adaptation benefits can be considered as co-benefits of projects, and we propose that adaptation project developers should be able to benefit from cash flows from the generation and sales of adaptation benefits. Revenues from such sales would boost the early adoption and dissemination of adaptation technologies and solutions, and accelerate host countries’ transition to low-emission, resilient and sustainable economies. Adaptation cash flows would also create a powerful market-driven incentive for private sector investments in adaptation measures.

However, there is a key difference between emission reductions and adaptation benefits. Emission reductions can be reported in a single fungible and internationally tradable outcome expressed in tonnes of C02 equivalents, but adaptation benefits are not fungible, being context- and project-specific, unique for each adaptation action. This difference has fundamentally altered the international community’s approach to adaptation, with the lack of comparable metrics contributing to the absence of a structured financial mechanism.

In our view, the challenge is not about how many adaptation benefits can be generated, but rather how much money can be mobilized to create genuine adaptation benefits which help developing countries adapt to climate change. Efficiency in this process can be measured by the ability to develop effective context-specific solutions and the leveraged private sector co-financing that can be mobilized by payments for adaptation benefits.

There are many reasons to expect demand for real adaptation benefits to grow in the near future.

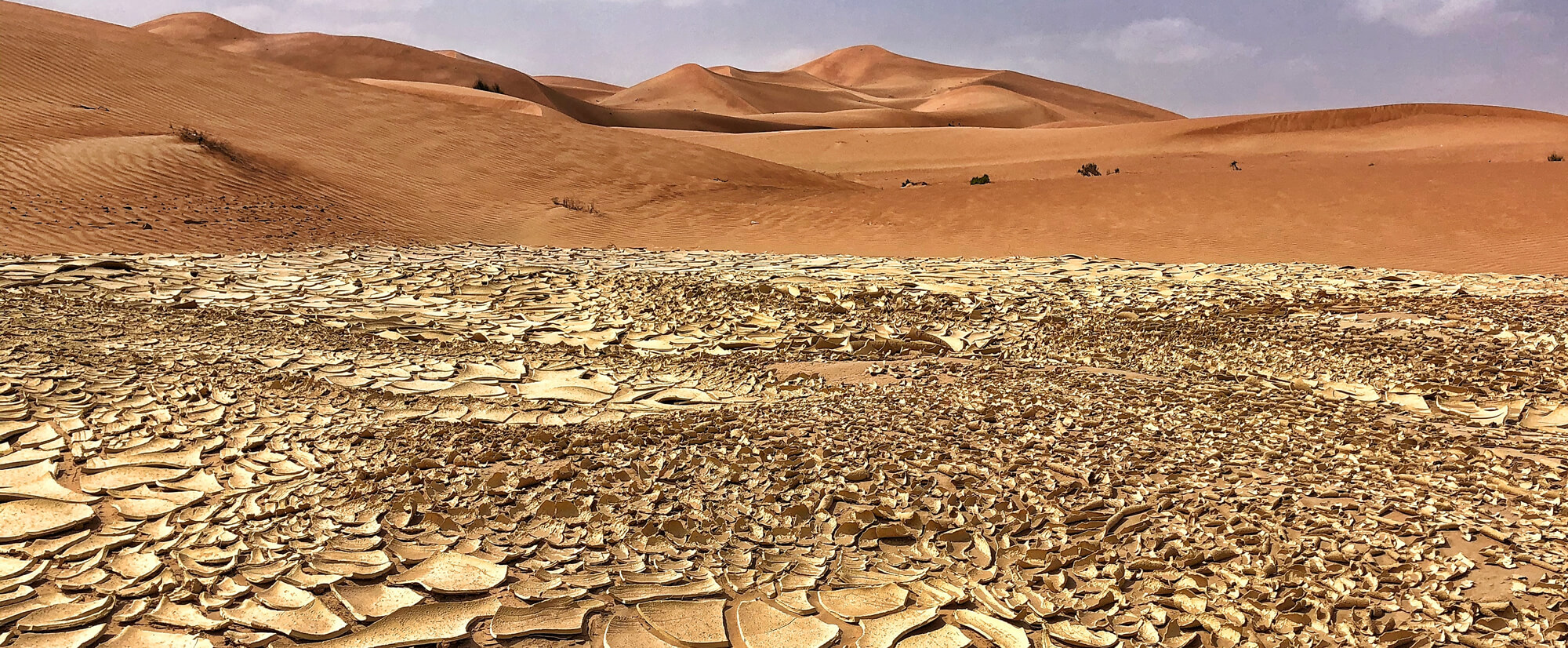

- The negative impacts of climate change, from which the developing world suffers disproportionately, are growing. Failure to help developing countries adapt will result in the loss of development gains and encourage radicalization, civil conflict and migration in the most affected African countries.

- National development priorities, the SDGs and other international treaty goals cannot be achieved without addressing adaptation.

- The Paris Agreement introduced new global goals on climate finance and adaptation; progress on the new targets must be concrete and demonstrable.

- As with mitigation under the Kyoto Protocol, governments may choose to delegate responsibility for achieving parts of the Paris Agreement goals on adaptation and climate finance to the private sector. This will require enhanced accountability.

- Most developing countries have included adaptation needs and priorities in their NDCs. While some efforts will be unilateral, international cooperation in specific adaptation and support will be necessary. In time, these needs may be transferred to adaptation communications.

- The Paris Agreement requires periodic updates of NDCs to reflect increased ambition over time and to maintain transparency in its path towards realizing the NDCs. While developing countries have to report on support received, developed countries must report on support provided, including for adaptation.

- Many private sector companies have committed to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and to global reporting schemes on climate action. The need to show progress requires quantifiable and transparent achievements, including adaptation.

- Non-profit organizations and individuals will want to make a difference and to pay for adaptation benefits that deliver credible information on impacts and value for money.

How can we help to accelerate and improve investment in adaptation measures by the international community? One sure way will be through the Adaptation Benefit Mechanism (ABM), developed by the African Development Bank with the support of the governments of Uganda and Cote d’Ivoire and the Climate Investment Funds, and currently being piloted from March 2019 to 2023.

The ABM will provide a credible and transparent vehicle for the definition, monitoring, reporting, verification, certification and issuance of unique host country approved adaptation benefits. An ABM board and methodology panel will guide and facilitate the development of ABM baseline and monitoring methodologies by the project developers, project registration and the generation of certified adaptation benefits. The approval process includes host country approval and independent third party validation. The Bank is providing secretarial support to the ABM board and methodology panel and will maintain a web-based information platform, ABM registry and a database of incremental costs for various adaptation measures.

The ABM offers the prospect of an “adaptation supermarket”, selling issued adaptation benefits and off-take agreements for future delivery, each adaptation benefit having its own unique adaptation story, co-financing leverage, and price. Donors, philanthropies, CSR stakeholders and individuals are invited to select and purchase their preferred choice, with the revenues going to the project developer to overcome the barriers to the implementation of the technology. Data collected at the ‘check-out’ will report public and private sector finance mobilized for adaptation from donor countries and host countries, leverage ratios, as well as associated impacts and contributions to the SDGs. These data may be used by countries to report against Paris Agreement commitments and obligations.

The ultimate goal of the ABM is to create a credible and transparent mechanism with which governments can pay for adaptation and, if they wish to, devolve the responsibility for paying for adaptation to polluters. Governments may use a variety of instruments including regulation, tax or levy to collect such funds and report amalgamated data. They should be encouraged to do so.

English

English

Français

Français